On Saturday 3rd May 2025 we held our first May Day Partisans Party ( https://www.facebook.com/events/1017101966935306 ) to launch the North East branch of the Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d’Italia UK (ANPI UK) – https://anpi.org.uk/en_GB/

It was established on 6th June 1944, in Rome, by the CLN of Central Italy, while the North was still under Nazi-Fascist occupation. On 5th April 1945, with the lieutenant decree n. 224, it was given the qualification of moral entity that endowed it with legal personality, promoting it in fact as an official association of partisans.

The Baker’s Prayer

Give us this day

our daily bread

and bless the lady baker

who makes it so perfect,

risen with love

in the face of fascists

and their poliziotto pals,

arms raised in the air,

saluting the foes

of their grand daddies’ nightmares.

Give us this day

one brave human being

who knows all the ingredients

to the bread of life:

the wheat off the land

shared out among people,

heaven’s fat raindrops,

a pinch of salt,

a wink of yeast,

a blaze of the sun,

a smidgen of patience,

a big dollop of care,

all keeping us from hunger

as we stand strong as

a Roman Emperor’s wall.

Give us this day

our daily bread

shared equally around

as we beat back the crowd.

Meld us together

as one kin, one clan,

one movement, one wall.

No Pasaran!

I am grateful to Harry for giving me permission to publish this very special tribute.

Alfio was so pleased that he has celebrated this poem in his article in Patria Indipendente the periodical of the National Association of Italian Partisans; the article can be found here – https://www.patriaindipendente.it/servizi/il-profumo-del-pane-antifascista-di-lorenza-e-arrivato-anche-in-inghilterra/

The scent of Lorenza’s anti-fascist bread has also reached England

Initiative in Middlesbrough, a town in the county of Yorkshire, promoted by the writer Tony Fox, with the participation of ANPI London created emotion and great interest in the people present, who had the opportunity to gain information on the episode of Ascoli Piceno, on the battles of today’s anti-fascists and on the history of the Italian Resistance. Among the audience there was also the famous English poet Harry Gallagher, who dedicated a poem to the baker of Ascoli: “The Baker’s Prayer”

The message of the baker from Ascoli Piceno who, on the occasion of Liberation Day on April 25, had displayed a banner with the words “As good as bread. As beautiful as anti-fascism” has also reached England. For this gesture of solidarity in memory of partisan relatives, Lorenza Roiati was questioned twice by the local police. Plainclothes officers wanted to identify her, inviting her to take responsibility for those words explained in front of her shop. She clarified her position by filming the scene, especially concerned about knowing who had ordered them to intervene. Let’s reread the writing: “April 25. As good as bread. As beautiful as anti-fascism”. Any violation of the law? Any disturbance of public order?

I rekindled the image of that banner while I was on the train that took me to Middlesbrough, a town in the county of Yorkshire 349 kilometres north of London. Until a few months ago I would never have imagined that I would find myself in charge of bringing the word of the ANPI to that part of the United Kingdom. But the London section has made its way in recent times by encouraging new contacts: Edinburgh, Dundee, Belfast, Manchester and now Middlesbrough. It is a little surprising to see the president of the section, Simone Rossi, acting on zoom from London among interlocutors as if he were connected to the whole country, except Wales, but it is probably only a matter of time.

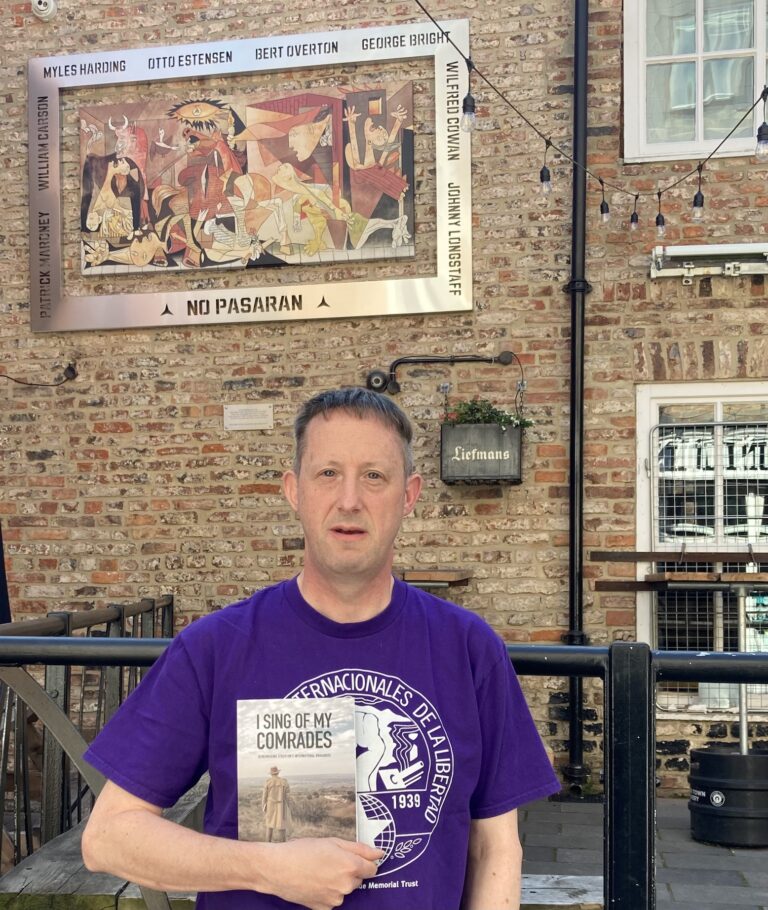

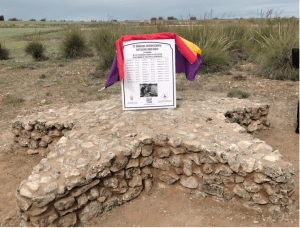

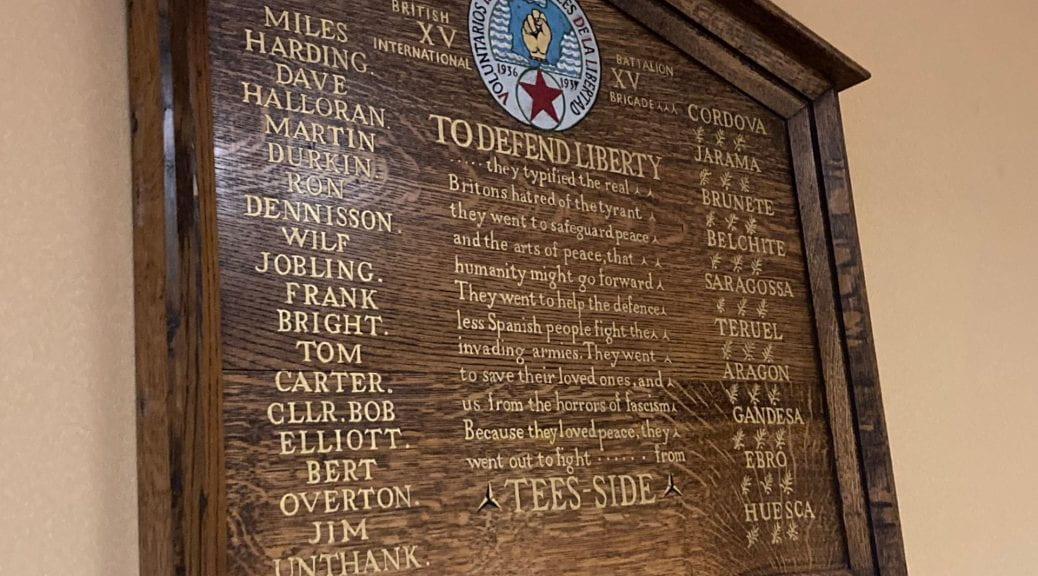

The invitation to the Middlesbrough meeting came from Tony Fox, a writer and journalist, as well as a seasoned anti-fascist activist. He is one of the founders of a local organisation called North East Volunteers for Liberty . On arrival he took me to a pub. “Look around,” he said, “what do you think?” On the brick wall in the very busy courtyard I saw a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica complete with a slogan to remember the English Fallen of the International Brigades. “It’s still fresh,” he smiled, visibly proud, “we’re getting busy.” It made me wonder if anyone in Italy has ever placed ‘Guernica’ in front of the customers of a bar or café in memory of the Italian Fallen of the International Brigades, of which there was certainly no shortage.

Tony explained how he thought it appropriate to ask the London ANPI to send a representative to illustrate the Resistance in Italy with a view to coordinating future cultural activities under the banner of anti-fascism and creating a local ANPI section.

There are Italian roots in the area around Middlesbrough which also includes Stockton-on-Tees across the river from the port. During the first half of the last century immigrants arrived from Italy who mainly worked in the food sector with restaurants, ice cream parlours and shops that still bear Italian names. Among them were also mosaic artists. They composed images of products or logos on the pavements that are still perfectly preserved.

This Italian presence in Middlesbrough did not leave bad memories. Unlike what happened in the major cities of the United Kingdom – Cardiff, Southampton, Liverpool, Glasgow, Birmingham, Dundee, Edinburgh etc. – where under the pressure of the London section of the fascist party founded in December 1921 the communities of Italians were annexed under the control of the fascist party, in Middlesbrough one could live relatively sheltered from strong pressure. Although kept under observation by the embassy, consulate and fascist party, the Italians in this area could exempt themselves from feeling obliged to demonstrate active participation in demonstrations with their arms raised as happened elsewhere. Perhaps this is why in Middlesbrough and the surrounding areas there are not many memories of Italians in black shirts.

In fact, in the Chapel’s meeting room I spoke to an entirely English audience. I am used to it. But when the subject touches on the Second World War I continue to feel marked by the awareness that I am addressing representatives of a nation that left thousands of Fallen on the Italian front, about 50,000 if we also count the soldiers of the Commonwealth. I feel obliged to recall first of all the stab in the back that Mussolini gave to England on 10 June 1940 and his cowardice in waiting for the moment in which Germany already seemed victorious with the prospect of a conspicuous spoils to divide.

After having illustrated the history of the Resistance between 1943 and 1945 and the role of the partisans in coordinating operations in contact with the Allied Forces and the agents of the English SOE (Special Operation Executive), who were parachuted behind the front lines to prepare the ground for the advance of the troops, I focused on post-war fascism, which never died, but rather, fuelled and reinvigorated by political manoeuvres and historical revisionism. I ended by mentioning some contemporary aspects of the activities of far-right groups, showing the film of a demonstration in Milan during which the Nazi-fascist salute was made. Not the “Roman” one, which does not exist.

In contrast, I told the story of the baker from Ascoli, explaining the meaning of the writing on the banner. When the words were translated into English, the room erupted in applause directed at her, followed by a moment of amazement when I explained the sequel with the intervention of the police and the request for identity documents, almost as if she had committed some sort of offence or punishable action. “On the next occasion of 25 April we will send the baker a message of support from Middlesborough, leaving it up to her to decide whether to display it in the window,” Tony said. “If we could do so, we would gladly buy bread from her bakery.”

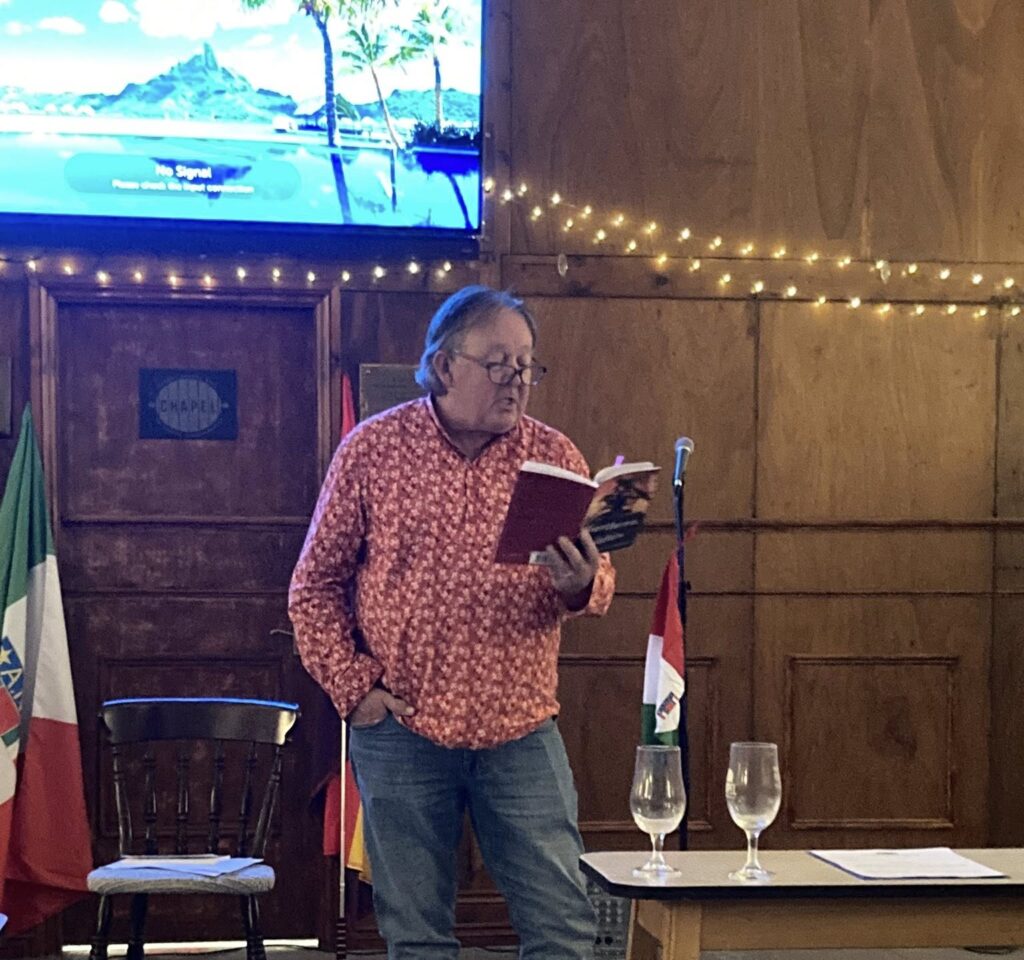

Also in the room was a well-known poet, Harry Gallagher, who seemed impressed by the episode. At the end of his speech with a recitation of his and Bob’s poems some dedicated to the Fallen of the International Brigades in Spain, Harry said he felt inspired by the gesture of the Italian baker to want to dedicate some verses to her. “If she likes them I hope she will display them next to her good bread in memory of the English soldiers and those of many other countries who lost their lives to liberate Italy”.

He sent me the poem. It is clear from the first lines that what struck him was the image of bread, a source of life, so much so that it is even considered sacred. To the hands of the baker, lowered and joined to knead love into bread, he contrasts those raised by today’s Nazi-Fascists to pay homage to persecutors who inflicted nightmares on their grandparents. In the lines, the baker kneads history and her thoughts into bread. She adds anti-fascism as an ingredient whose necessity she knows with a good dose of daily opposition. Because she knows that in the corner, in modern clothes and with persuasive language, the same forces that have mowed down freedom and dragged millions of people towards death are popping up again. She is aware that there are minds at work on another nourishment that Mussolini called Strength with a mixture of violence.

Some lines require interpretation. Against fascism the poet urges opposition “as strong as a Roman emperor’s wall”. He refers to the wall over one hundred kilometres long not far from where he lives that was built under the emperor Hadrian and that continues to be visited by millions of people who walk along its lengths. More than symbolizing the point where the force of the Roman invasion had to stop in front of the opposition, in its mixture of earth and rock today the construction evokes massive permanent resistance.

And how can the oxymoron of the prayer in struggle be rendered in Italian? “ Give us this day/our daily bread/shared equally around/as we beat back the crowd”. Is it enough to translate “Dacci oggi il nostro pane quotidiano condiviso intorno mente respingiamo la folla”? No, because the term crowd/mob alludes to collective power in the sense of a threat to freedom of movement or expression. I chose “mentre respingiamo la brigata” with the reference to the black brigades. Gallagher’s poems always end up published so The Baker’s Prayer , will need an explanation at the bottom of the page to be understood. So there will be the name of Lorenza Roiati and the reference to her gesture for April 25, an event that frankly in England is rarely talked about.

Thus poetry celebrates the Resistance, teaches and watches. This is already a great result. Trying to go further and make the historical-environmental sense of the partisan struggle and its continuation intelligible abroad is almost impossible. In Middlesbrough I tried again. “These feet that brought me before you have touched the earth of the mountain paths in the Romagna Apennines where I come from,” I said, “they took me to visit the places where the partisans operated in the stretches between the woods from one farm to another where they could trust the farmers, find refuge, feed themselves.”

Taking advantage of the listening I added that it was precisely the very Italian meaning of the partisan’s path that some years ago induced me to write to the Mayor of Predappio to propose a modification to the local fascist house that was inaugurated in the week of the bombing of Guernica and that today seems reduced to a sort of ruin. “Let’s bring it to life – I wrote to him -, let’s divide it in half and make a simple path covered with grass pass through the middle from one side to the other”. I saw among the audience in Middlesbrough some perplexed, perhaps moved, faces. Poetry takes you far.

Alfio Bernabei, Anpi London, is the author of Esuli ed emigrati italiani nel Regno Unito 1920-1940 –“Italian exiles and emigrants in the United Kingdom 1920-1940” (Mursia) and the historical novel L’estate prima di domani–“The summer before tomorrow” (Castelvecchi)

Harry Gallagher’s poem

The Baker’s Prayer

Give us this day/our daily bread/and bless the lady baker/who makes it so perfect,/risen with love/in the face of fascists,/arms raised in the air,/saluting the foes/of their grand daddies’ nightmares./

Give us this day/one brave human being/who knows all the ingredients/to the bread of life:/the wheat off the land/shared out among people/heaven’s fat raindrops/a pinch of salt/a wink of yeast/a blaze of the sun/a smidgen of patience/a big dollop of care/all keeping us from hunger/as we stand strong as/a Roman Emperor’s wall/

Give us this day/our daily bread/shared equally around/as we beat back the crowd/Meld us together/as one kin, one clan/one movement, one wall/No Pasaran!

La preghiera del forno

Dacci oggi/il nostro pane quotidiano/e benedici la fornaia/che lo fa così perfetto/lievitato con amore/di fronte a dei fascisti/braccia alzate in aria/per salutare i nemici/incubi dei loro nonni/

Dacci oggi/un essere umano coraggioso/che conosce tutti gli ingredienti/del pane della vita/il grano dalla terra/condiviso tra la gente/grosse gocce dal cielo/un pizzico di sale/un po’ di lievito/un raggio di sole/un’infarinata di pazienza/una bella cucchiaiata di attenzione/l’insieme per proteggerci dalla fame/mentre forti ci teniamo/come muro d’imperatore romano/

Dacci oggi/il nostro pane quotidiano/condiviso a tutti intorno/mentre respingiamo la brigata/Impastaci insieme/come tutti parenti, tutti una famiglia/un solo movimento, un solo muro/No pasaran!

(Translation by Alfio Bernabei)

Alfio

Alfio

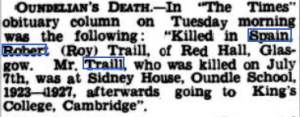

The American section of 20th International Battalion, Possibly Robert Traill standing first from the right

The American section of 20th International Battalion, Possibly Robert Traill standing first from the right

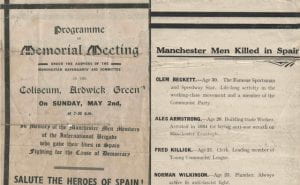

Daily Worker, 29th July 1937 –

Daily Worker, 29th July 1937 –

7 Alma Place, North Shields

7 Alma Place, North Shields

The Golden Smog, Stockton-on-Tees

The Golden Smog, Stockton-on-Tees

A copy of I sing of my Comrades in Madrid

A copy of I sing of my Comrades in Madrid

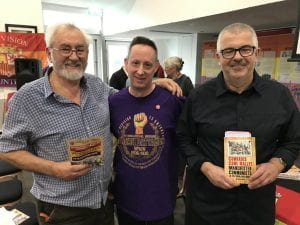

Alan Short, Nic Maroney, Mich Maroney, Barbara Sneath, Katie Quigley, Chris Hill and George Short.

Alan Short, Nic Maroney, Mich Maroney, Barbara Sneath, Katie Quigley, Chris Hill and George Short.