This is a special guest blog from David Walsh

On 5th September 1911, a group of thirty or so boys marched out of Bigyn council school in Llanelli in West Wales to protest over the caning of one of their peers. Within days, pupils in more than sixty towns throughout Britain had taken to the streets to express their grievances. And many of these protests and walk-outs also happened here in the North East

The school strikes of 1911 took place during a time of widespread industrial unrest. Llanelli itself had witnessed a traumatic strike of local railwaymen, with 600 soldiers sent into the town to keep the peace, but which only led to rioting and several fatalities.

The same was true in the North East. Early in that year there had been a stoppage by dock workers which shut the ports of Middlesbrough, Hartlepool and Sunderland. This was then followed by a North East seamen’s strike and climaxed with the region’s railwaymen walking out as one – an action which led to troops being deployed in Darlington and East Cleveland and to railway services coming to a total standstill.

Children were not immune from all of this – many parents were directly involved as employees within these industries. They were also aware of the emerging adult labour movement – as one boy told a Daily Mirror reporter, ‘our fathers strike – why shouldn’t we?’ But should the strikes of 1911 be seen merely as copy-cat protests?

The particular incident which triggered the first strike in 1911 was the hitting of a child by an assistant teacher in the absence of the Headmaster, who was away from school on sick leave. By the end of the week the strike had spread to schools in the big cities of Liverpool, Sheffield, Birmingham, London, Glasgow and other cities. The remarkable speed in which the strikes developed was often blamed by local councillors on the newspapers. While some of the protests were violent – for instance, boys in the East End of London were armed with sticks, iron bars and belts – the vast majority were peaceful affairs.

The Northern Echo covered the issue thoroughly, although initially with a degree of levity. The first reports on the 11th September covered schoolboy strikes in South and East London, Grimsby, Colchester and even Dublin, observing that the central demands were for the abolition of the birch and the cane, then still in wide use, and for payment for homework – a penny a day was suggested.

Clearly this publicity did not go unnoticed by local schoolchildren, and by the 14th, the first school strikes in the region – at Stockton – were reported, with a description of boys from Oxbridge Lane School walking out to hold an impromptu march through the town, parading with posters calling for a reduction in school hours, the abolition of the cane and payment of a penny a day for monitors. The Echo reported that the authorities, in the shape of Attendance Officers, the dreaded ‘school board men’, called on the parents of the absent pupils to ensure no repeat took place. Whether this had any real impact is hard to gauge – certainly by the same evening, the Echo was reporting that the very same boys were back, this time marching through Stockton High Street.

Oxbridge Lane School about 1932, from https://picturestocktonarchive.com/

Oxbridge Lane School about 1932, from https://picturestocktonarchive.com/

By the following day, the strike fever reached Newcastle, where senior pupils at the Sandyford Road Council School struck demanding the abolition of homework. In the report it was said that “the headmaster’s stance, refusing to consider the application, led to the boys holding meetings outside the school and on the town moor. Similar occurrences occurred on the other side of the Tyne involving a number of boys at the Gateshead Council and National Schools who also ” struck.”

Similar events occurred at Middlesbrough and York, where the demand was for ‘less work and less stick’.

Things in the Hartlepools took a more serious turn, with the London Times reporting that 100 boys at the Galleys Hill council school ‘came out’ and ‘that a storage room at the back of an hotel was looted and some bottles of stout and whisky and boxes of cigars were removed by the “strikers” some of whom were arrested and will be charged this morning….…The boys are also stated to have thrown stones at the windows of houses occupied by the teachers.”

The same paper also reported that “at Middlesbrough a procession of young “strikers” was dispersed by the police, who seized the placards they were carrying. Over 100 boys marched from school to school trying to bring others out and stones were thrown into one of the playgrounds where lads were drilling.”

This was borne out by reports in the then Middlesbrough Daily Gazette which identified the schools at the heart of the trouble as being “in the Newport District” and also observing that slogans were being chalked on school walls, and that, wonder of wonders, “they were both neat and correctly spelt”.

By the 18th the contagion had spread to Darlington and South West Durham. The Echo reported that “A number of the older boys at Harrowgate Hill School walked out of classes after the first lesson’, then, with what the paper said was a ‘meagre number’ leaving the school at midday to march to Rise Carr School where they linked up with a similar group who had also struck class, to hold a public meeting at a nearby street corner”.

This meeting must have been witnessed by an Echo reporter, as the account stated that the demands put forward there were for ‘a penny a week for all children and a four day school week’. The Echo observed that they ‘may have to wait a long time for this’ and acidly observed that ‘in the meantime it was voted as good fun to hold their meetings and defy teachers from the safe side of the school wall.’

The following week saw Echo reports of similar actions in South Shields where the majority of schools in the town were out, and where the police, robustly, corralled students back to class, and at Shildon, where schools in the town were picketed by pupils from the outlying Black Boy and Eldon schools, action which resulted in a ‘small number of students at the Shildon Council School joining in a march through Shildon under the slogan of ‘strike, strike and strike a blow for freedom.’

But by the following week, the strikes, save for a small reported flare up at Crook, were over, with pupils back at the chalk face, and their demands unmet.

But by the following week, the strikes, save for a small reported flare up at Crook, were over, with pupils back at the chalk face, and their demands unmet.

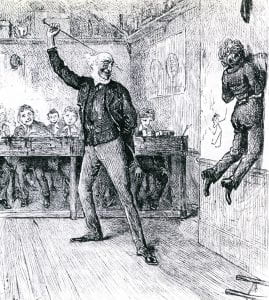

The 1911 school strikes shouldn’t be overplayed. Numerically, while thousands were involved nationally they represented less than one per cent of the total school-age population. Their significance doesn’t relate to numbers – but the fact that many young people felt that they had to speak out on the issues that concerned them – and this, almost everywhere, centring around the practice of corporal punishment – the strap, the cane and even the birch.

It was also noticeable that all the stoppages in the North East related to what were called ‘council schools’ – that is, schools set up by the local authority, and given increased power through the earlier 1902 Education Act. The strikes did not seem to affect either the more middle class and exclusive church schools or local Grammar Schools, and the protests seemed to occur entirely in working class areas of the region. Also noticeable was that the press reports spoke uniformly of “School Boys” – there was no mention of any involvement of girls from the strictly segregated all-girls council schools. Was there any ?

An image from Hull, School Strike 1911

An image from Hull, School Strike 1911

There can be no doubt that these were genuine grievances. In following years some school authorities recognised the serious nature of the strikes and looked for ways to improve home-school relationships, against others who called for a firmer hand. In wider society, reforms to improve welfare provisions for children were well under way but corporal punishment remained the mainstay of controlling pupils for many teachers until as late as the 1970’s and the 1980s.

While schools today are required under the National Curriculum to provide opportunities for pupils to discuss a range of social issues, for instance in citizenship lessons, or through the setting up of School Councils, it is clear that, evidenced by school student protests over the future College Fees they will face, this is seen by many pupils as a mere token provision.

So, the decision to walk out of class and march through the streets – as we have seen in more recent years – remains the most dramatic form of pupil protest.

And the schoolboy strikers at Oxbridge Lane, Newport, Harrowgate Hill, Galleys Hill and Eldon – as well as all the other schools cited ? Tragically the leavers classes of 1911 were also the conscripts of 1916 who were then to face, not the cane, but the machine guns, gas and the barbed wire at the Battle of the Somme.

David Walsh

Citation from the Times Archive

15/09/11

At West Hartlepool about 100 boys at a council school ” came out.” A storage room at the back of an hotel was looted, and some bottles of stout and whisky and boxes of cigars were removed by the “‘ strikers,” some of whom were arrested and will be charged this morning. While marching through the streets the boys stopped an errand boy who was taking some apples to a house and helped themselves freely to the fruit. The boys are also stated to have thrown stones at the windows of houses occupied by the teachers. At Newcastle-on-Tyne yesterday afternoon the bigger boys at Sandyford-road Council School “struck,” demanding the abolition of home work. The head master refusing to consider the application, the boys held meetings outside the school and on the town moor. A number of boys at the Gateshead Council and National Schools also ” struck.” At one school they demanded the payment of a penny to each from the rates every Friday afternoon. At Middlesbrough a procession of young ” strikers” was dispersed by the police, who seized the placards they were carrying. Over 100 boys marched from school to school trying to bring others out, and stones were thrown into one of the playgrounds where lads were drilling.

16/09/11

The schoolboys’- strike ” showed signs of dwindling yesterday, and in many cases the returning truants were severely punished by masters or parents. The “strike” in Newcastle-on-Tyne was ended yesterday. The boys returned to their lessons in the morning, most of them bringing notes stating that they had been punished by their parents. They also received lectures from the school managers.