Some may have seen my campaign for recognition for George and Phyllis Short – The power couple of Teesside communism where I am aiming to mark the work they undertook to improve the lives of the people of Teesside, they helped the disadvantaged on Teesside for a period of fifty years.

This week, the ever wonderful Peter Verburgh pointed me towards a series of documents which are fascinating, I have ran out of extolments for Peter; he discovered the medical records for Bill Carson and Patrick Maroney which explained why they were repatriated – see I Sing of My Comrades: Remembering Stockton’s International Brigaders

Peter’s brief and precise message was :

495/14/211 & 212 for material on the N.U.W.M. and the 1936 Hunger March ( period February-December 1936 )

This took me to André Marti’s personal file in the Moscow archives, Marti was a leading figure in the French Communist Party (PCF), who, in 1936, became the Chief Political Commissar of the International Brigades operating the Brigade headquarters and training base at Albacete. Looking in this folder is unusual as we spend most of our time in the RGASPI. F. 545 folder which is the folder for the International brigades.

The first document that caught my eye was a letter dated 22nd October 1936. I knew that this was whilst the 1936 National Hunger March was on; it started in Aberdeen on 26th September and finished in London on Sunday the 8th November. The part of the letter that especially caught my eye was the name of Ellen Wilkinson.

Ellen Wilkinson is of especial interest, when in October 1924 Ramsey MacDonald’s Labour government resigned, after losing a confidence vote in the House of Commons, the ensuing general election was dominated by the “Red Scare”. The previous year the Labour Party had proscribed the Communist Party and outlawed dual membership, Ellen Wilkinson left the CPGB and was selected as The Labour Party’s candidate for the constituency of Middlesbrough Eas. At the General Election Labour’s representation in the House of Commons fell to 152, against the Conservatives’ 415, with Ellen Wilkinson being the only woman elected on the Labour benches.

Whilst MP for Middlesbrough East Ellen continued to promote policies which were not official Labour Party policies, but which were being advocated by the CPGB; for example she promoted birth control, a measure the CPGB central committee had been promoting since 1922 and which the The Labour Party renounced, it is suggested this was because The Labour Party feared losing the Catholic vote.

Whilst MP for Middlesbrough East Ellen continued to promote policies which were not official Labour Party policies, but which were being advocated by the CPGB; for example she promoted birth control, a measure the CPGB central committee had been promoting since 1922 and which the The Labour Party renounced, it is suggested this was because The Labour Party feared losing the Catholic vote.

She was ever the activist, In May 1926, during the nine day duration of the General Strike Ellen Wilkinson toured the country to promote and support the strike. She was furious when the Trades Union Congress called off the strike, and despite threats of expusion she continued to campaign for the Miners as they fought on alone: in June 1926 she joined George Lansbury at an Albert Hall rally which raised £1,200 for the benefit of the miners, who continued their strike for another five months.

Ellen Wilkinson’s reflections on the strike are recorded in A Workers’ History of the Great Strike , which she co-authored with CPGB member Raymond Postgate and her lover Frank Horrabin. Ellen also published the semi-autobiographical novel Clash in 1929 which is also set during the General Strike. The result was that Ellen Wilkinson was again threated with expulsion from The Labour Party, but she again called their bluff – the expulsion of the only female Labour MP immediately after women had gained the franchise by The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act in July 1928 would have been a political disaster.

There have always been strong rumours that Ellen Wilkinson continued to work closely with CPGB members after she had resigned her membership. I feel that this letter provides quite a bit of substance to these rumours, hence my excitement.

In The Jarrow Crusade: Protest and Legend Dr Matt Perry carefully lays out all the ways the organisers distanced themselves from the Communist organised National Hunger Marches, fearing that an association with the Communists would undermine their protest. They were largely successful; most people have heard of the ‘Jarrow Crusade’ (the word ‘march’ was not used to avoid associating with the Communist organised marches), but few people have heard of the fifteen National Hunger marches held between 1919 and 1936. I always find this remarkable as they are so different in scale: the Jarrow March started with about 200 men, whereas the National Hunger Marches usually had over 1,500 participants , with the highest being 2,000 men on the 1922 march. In fact the Stockton Contingent alone in the 1936 National Hunger March had more men than the Jarrow Crusade.

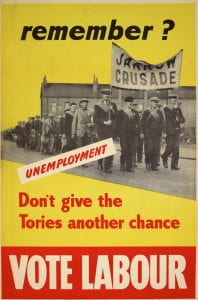

The Jarrow Crusade has since entered the iconography of the British nation, the image of a respectable, non-political, non-threatening form of protest; a representation of the marchers even appeared in the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony. But this bleached and de-politicised portrayal is far from the truth, the Jarrow Crusade was a small scale protest riding on the coat-tails of the NUWM’s campaign against government policy, especially the despised Means Test. The Jarrow Crusade was looking to rectify an issue that affected one town, whereas the decade long NUWM campaign was looking to alleviate a national problem.

The Jarrow Crusade wasn’t the only other march to arrive in London at the beginning of November 1936. The contingents of the National League of the Blind and the British Campaigners’ Association reached London at the same times as the Jarrow March and the National Hunger March, they too where welcomed by supportive demonstrations held for them at Trafalgar Square or Hyde Park.

The Labour Party has long been keen to use the example of the Jarrow Crusade to burnish its own reputation, with successive leaders seeking to give the Crusade a retrospective Labour Party gloss, just one example can be seen in this 1950 General Election poster.

But the truth is that in reality the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party and especially the TUC were very quick to distance themselves from the Jarrow Crusade. This was a continuation of the directives which forbad Labour Party members supporting Communust led protests against the Means Test, Unemployment and the BUF; the TUC was especially fearful of the NUWM which was organising the unemployed and therefore threatening their control over the unskilled and those with infrequent work.

Famously when Ellen Wilkinson proposed a motion in support of the Jarrow Crusade at the Labour Party Conference held at Edinburgh in October 1936 the motion was unsuprisingly blocked by the NEC, instead Hugh Dalton was charged with leading ‘an investigation into conditions in which people lived and worked, or did not, in the Special Areas.’ The Labour Party Conference opened on 4th October 1936 and the Jarrow marchers set off the next day on the 5th of October.

Councillor David Riley

Councillor David Riley

The opposition from the Labour Party and the TUC meant that it was left to local figures of the Labour left, such as Councillor David Riley, chair of Jarrow council, Ellen Wilkinson, and Paddy Scullion to organise the protest march.

The October 1936 letter suggests that lacking institutional support from the Labour Party Riley, Wilkinson and Scullion used the CPGB’s expertise and experience in orgainising their protest marches to aid them in their own protest march; it was intially planned that the Jarrow marchers would be a contingent in the National Hunger March. It could be argued that despite the appearance in reality the Jarrow Crusade was in fact little more than a contingent of the 1936 National Hunger March – it had the same purpose and was no larger than the 200 strong Stockton Contingent.

The Jarrow march had ended at Hyde Park on 1st November , however there was no official rally at the end, instead they joined a 5,000 strong Communist rally that was taking place to support the National Hunger March due the following week, and which this letter of 22nd October promotes .

The seven contingents of the National Hunger March, comprising 1,500 men and women, arrived in London on Sunday 8th November 1936 along with 250 marchers from the National League of the Blind. They were met by a crowd estimated to be about 80, 000. The National Government had decreed that newspapers should not publish stories or pictures of the National Hunger march, and as a result images are very rare. You will find, however, that this did not apply to the Jarrow Crusade, for which images seem multitudinous. I feel that this is a great shame, for it takes the Jarrow Crusade out of context, portraying it as a one-off stunt which although honourable, ultimately failed in its aim.

The Jarrow march was just one facet of the campaign to eliviate the suffering of industrial regions in the North of England, a campaign which had been ongoing for fifteen years prior to the Jarrow march. It is this campaign which these documents Peter directed me to highlight.

To avoid an overlengthy post I’ll return to this is a seperate post.